Attending the First Thursday art experience at the Nevada Museum of Art was absolutely beautiful. Coming from Los Angeles, I’ll admit – I didn’t expect to be so deeply moved by a museum in Northern Nevada. But I was. The architecture, the curation, the atmosphere – it all carried a modern elegance and a quiet, confident beauty that rivaled some of the best art spaces I’ve visited anywhere. The breadth of work on display and the museum’s sense of identity impressed me far more than I anticipated.

Meeting up with Sonni outside the museum, it felt that the time between our recent adventures together in San Diego was only a day ago – rather than a few months.

Immediately upon entering the museum I loved viewing and listening to the harp player in the foyer.

The hands-on block printing station offered a charming interactive element. We were both tempted to try it, but the music and rooftop experience were calling us louder.

The rooftop of the Nevada Museum of Art provides one of the most unexpected and beautiful views of Reno. Surrounded by mountains and city lights, it was incredible to see the local community gathered to support culture and creativity.

Sonni and I enjoyed a beer from a local brewery, Parlay Olé Mexican-Style Lager from Parlay6 Brewing Company, before beginning our walk among the exhibitions.

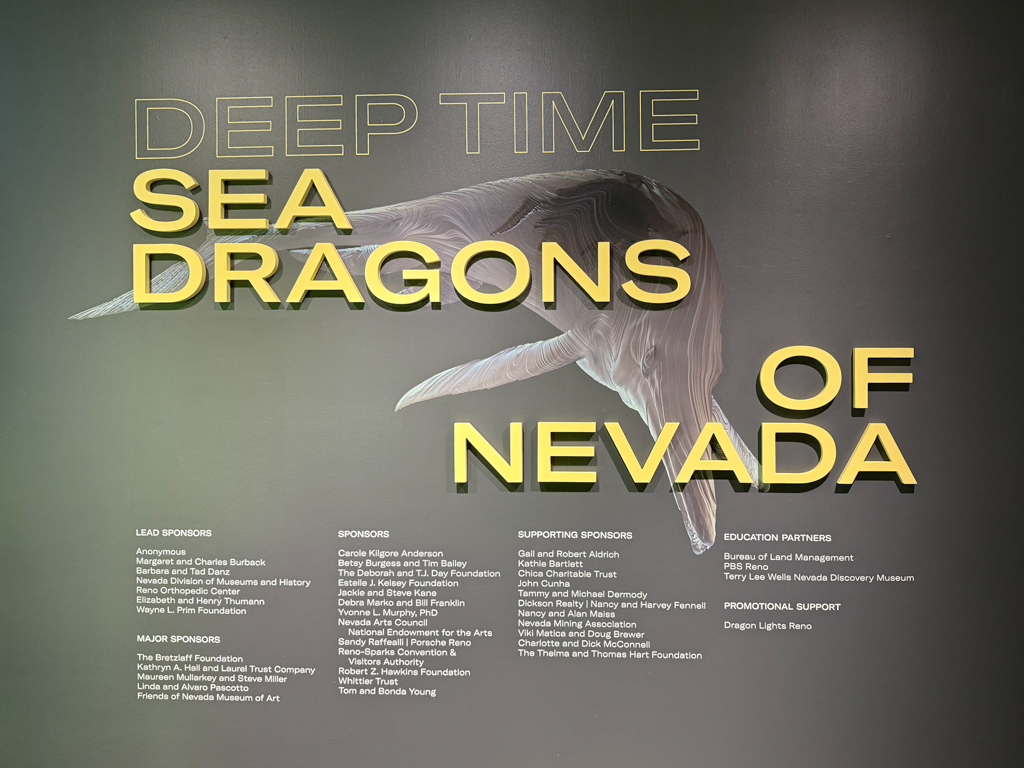

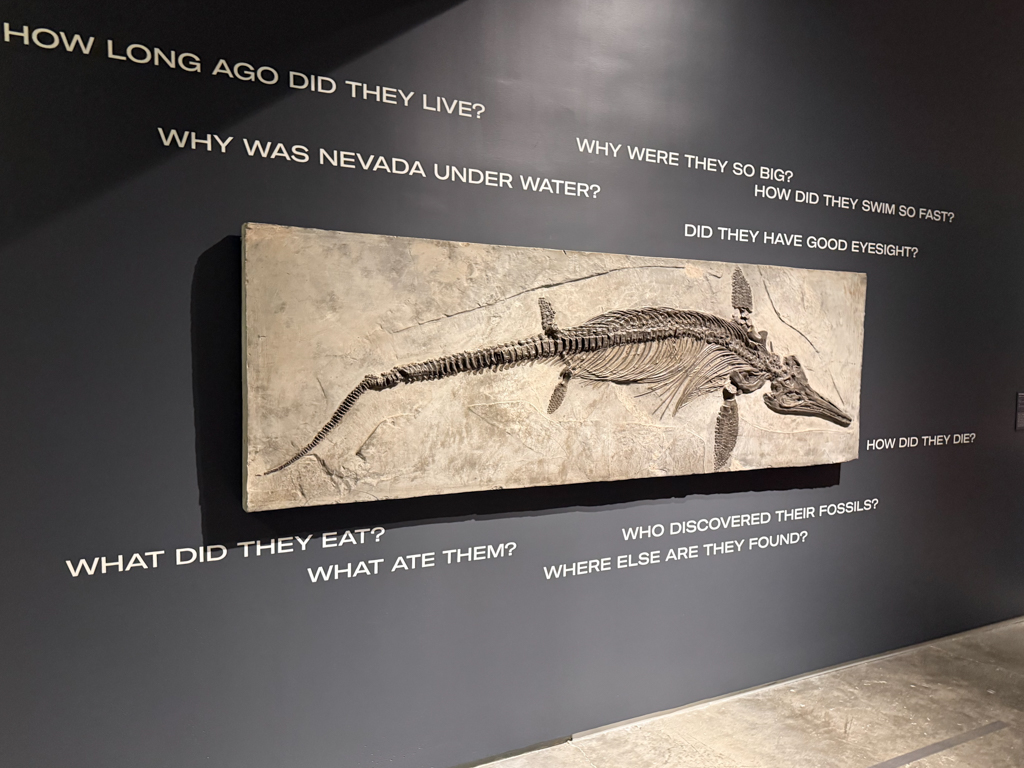

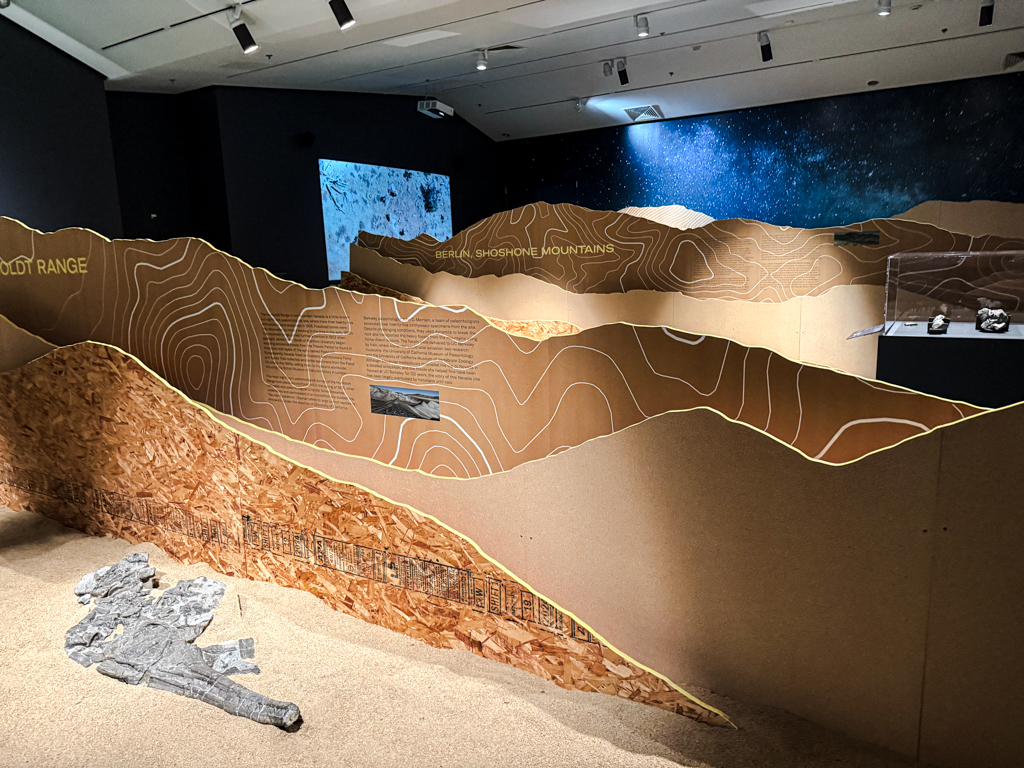

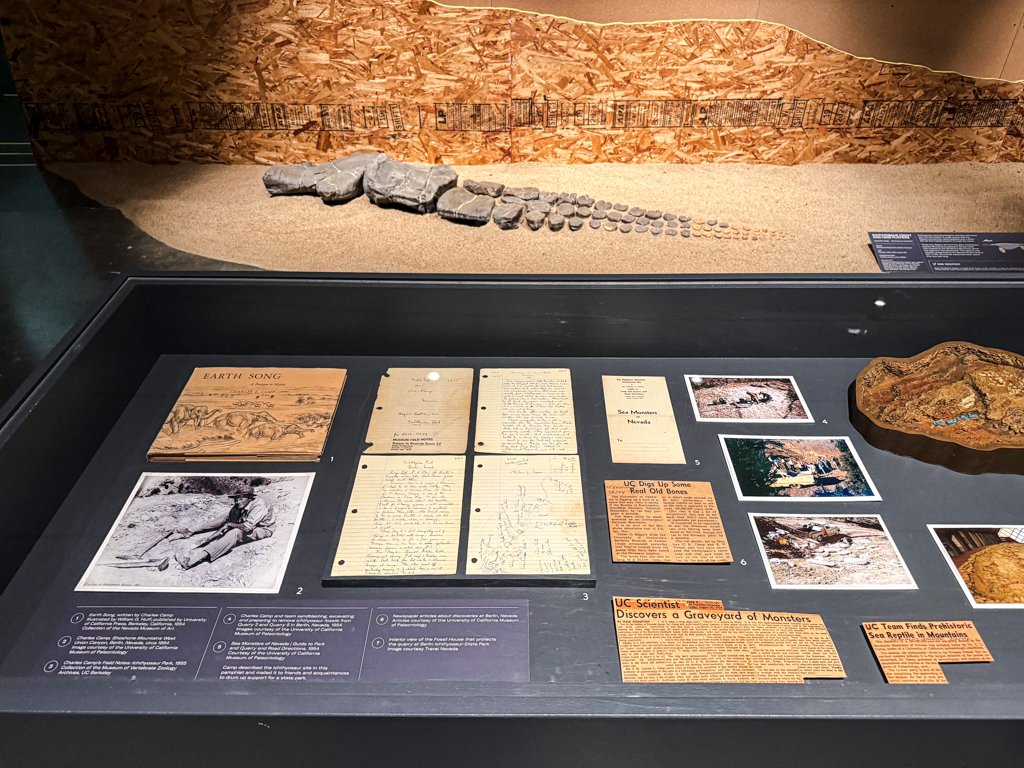

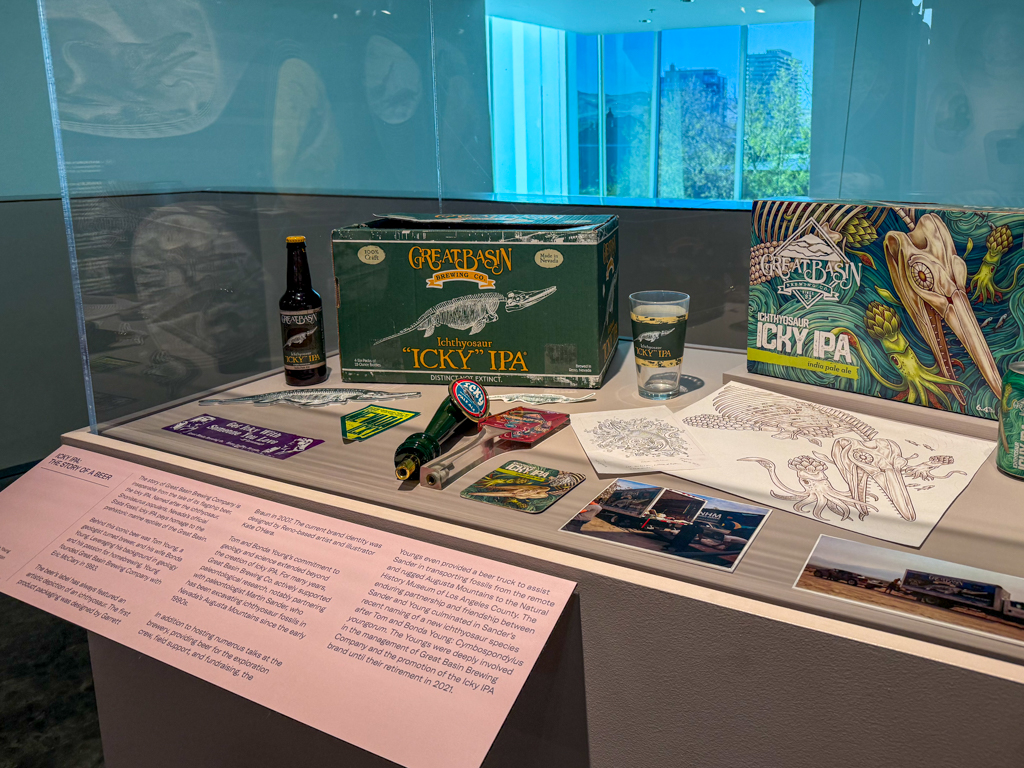

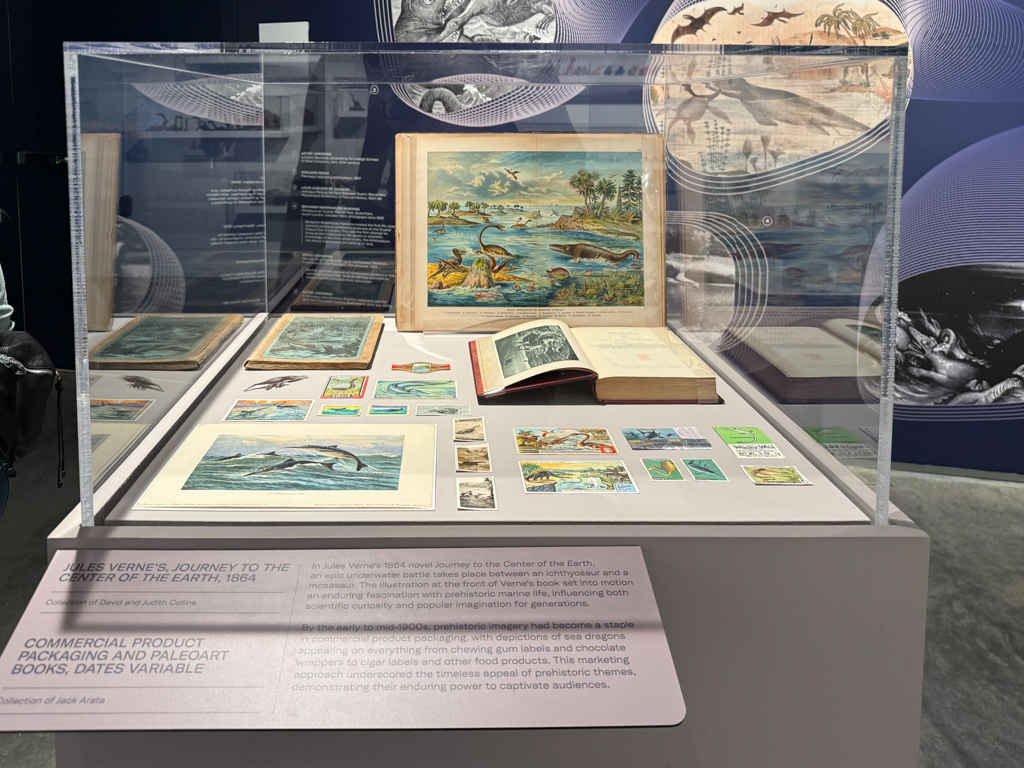

We began our exploration with the “Deep Time: Sea Dragons of Nevada” exhibit, and I can honestly say: my mind was blown. I had no idea that Ichthyosaurs -a species of massive marine reptiles – once swam through ancient seas where the Nevada desert now lies.

Learning that they were designated the Nevada State Fossil in 1977 was a humbling reminder of just how layered the land beneath our feet truly is. This exhibit didn’t just present fossils—it told a story of time, evolution, and the incredible history hidden within what many consider barren desert. The blending of science and art here was exceptional, making prehistoric life feel immediate and awe-inspiring.

Next, we wandered through “Fossils to Figures: A Boy’s Dinosaur Dream,” which offered a more personal lens on natural history and childhood wonder. The exhibit struck a softer, nostalgic chord—one that made me think about the dreams we carry forward from our earliest fascinations.

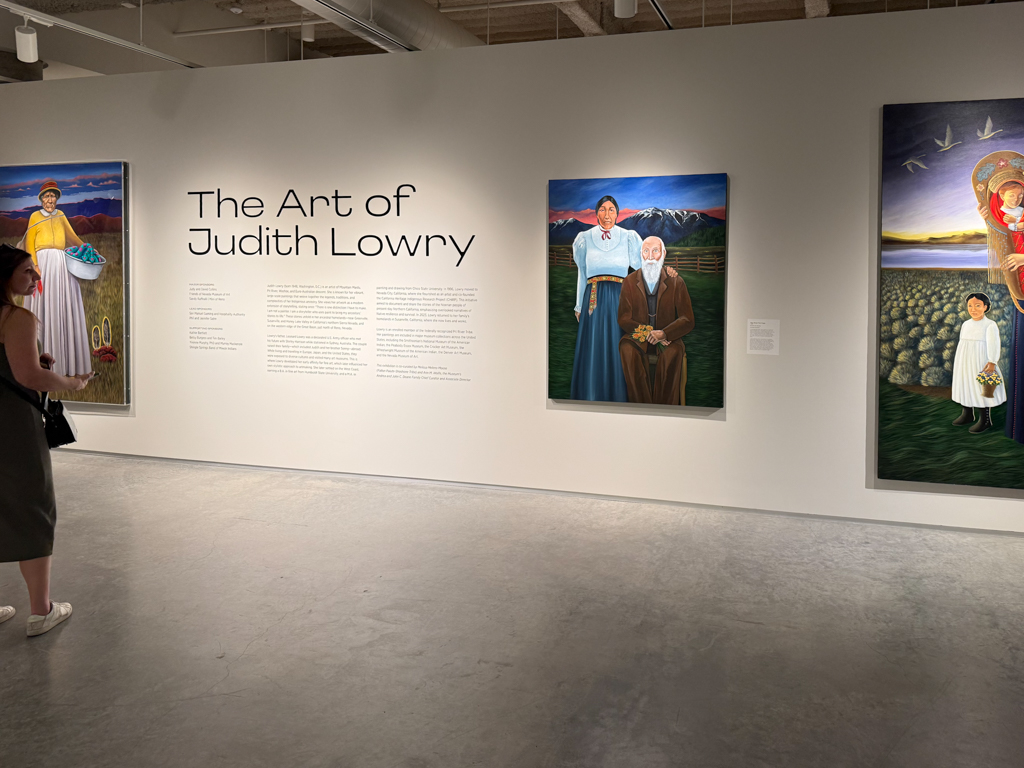

From there, we explored “Of the Earth: Native American Baskets and Pueblo Pottery,” seamlessly transitioning into “The Art of Judith Lowry.” The intricate craftsmanship and powerful cultural narratives woven into these pieces were visually stunning and spiritually grounding.

The visual thread continued into “Desert Dialogues,” which offered perspectives on land, identity, and resilience.

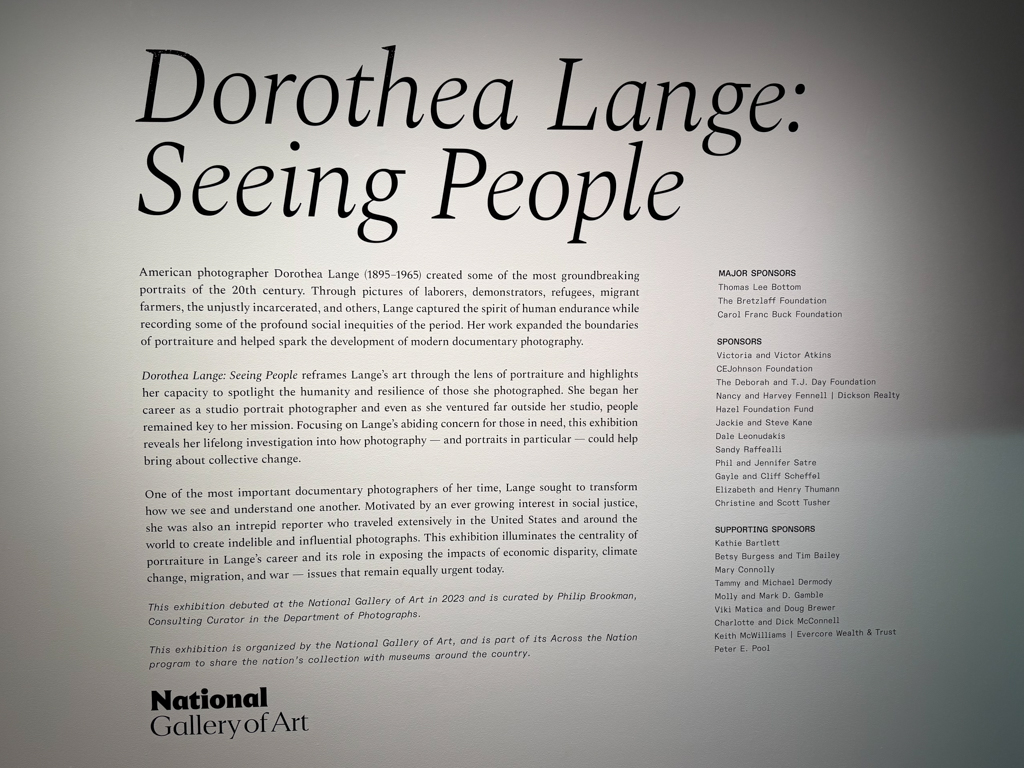

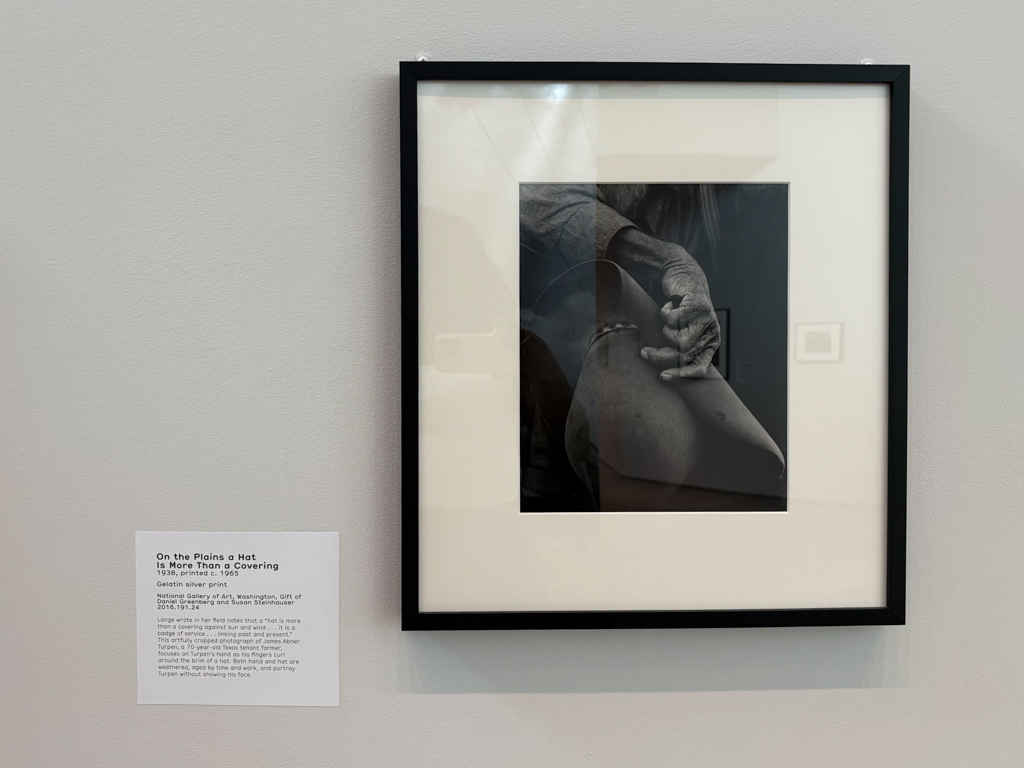

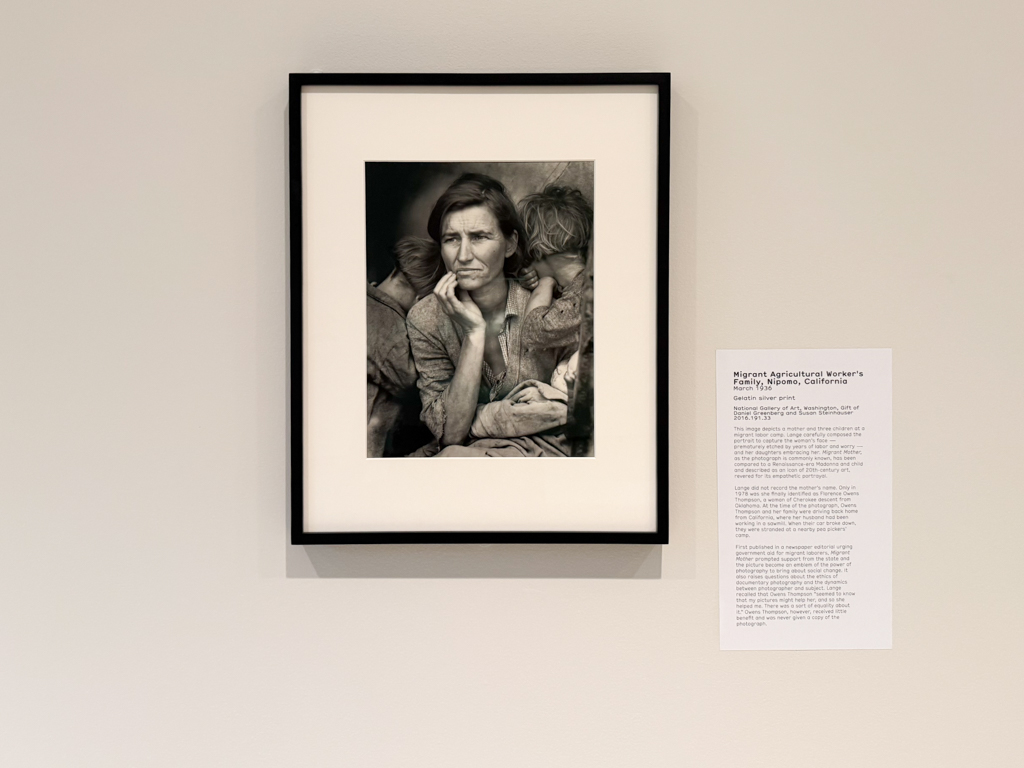

But it was “Dorothea Lange: Seeing People” that lingered with me the longest. Her photography didn’t just capture faces—it captured eras. Each image was a meditation on human migration, struggle, perseverance, and the American identity. Standing in front of those photographs, I found myself wondering: what moments are we chronicling now? What version of America are we documenting through selfies, status updates, reels, and fleeting captions? What phase of America are we casually snapshotting, posting and liking? What is this record- this time and place? Who are we, as a people and as a nation?

After immersing ourselves in the galleries, Sonni and I returned to the rooftop for another round of beer, ready to decompress and reflect. I fell into conversation with a friend’s boyfriend and we started talking about scars – physical and emotional, how we carry them and how we interact with the world in the shame of being marked.

In my case, I’ve been obsessed with one particular larger than I’d like scar, resulting from my laparoscopic surgery to remove fibroids from my uterus. In his case, it was a scar that marked his body from an incident when he was 15. In Sonni’s case, it was a bicycling scar that she’s market with a tattoo of a bicycling riding the scar to take power back from the incident.

It made me confront the narratives we’re told about “perfection.” That our bodies should remain untouched, unmarred. That we should quietly heal, without visible reminders. But those scars – those lines carved by healing and history – are part of our stories. My own scar is the evidence of a procedure that saved me from debilitating anemia, that helped me reclaim my health and my life. The art of science marked my body, changing me forever. It is not a flaw – it is a signature of science and survival.

That’s what good art does – shifts your perspective of yourself, of what’s possible and inspires the viewer. Instead of my scars challenging my interpretation of myself, I can see them as art.

I wonder what era of my life is yet to come.

Nevada Museum of Art

160 W Liberty StreetReno, Nevada 89501